Written by Delia Oltean –

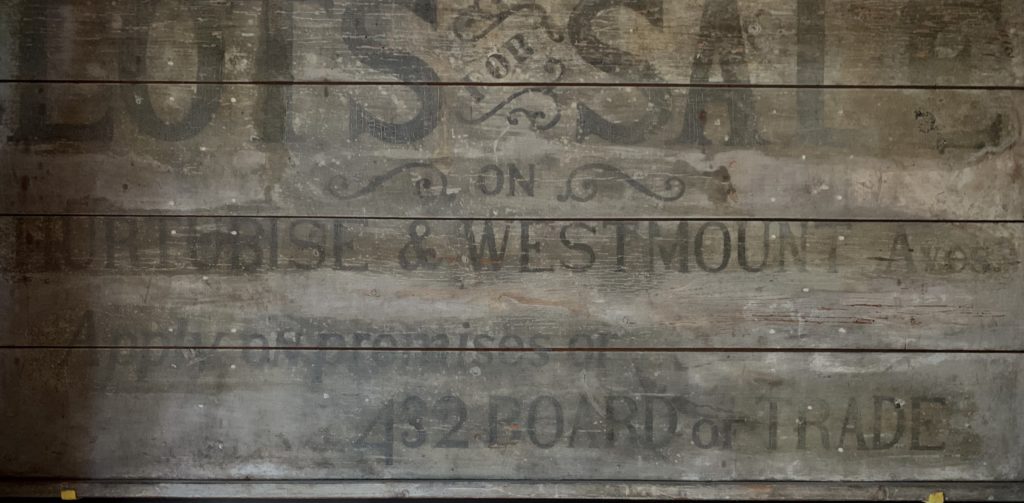

Looking at the frontage of the Hurtubise House is to look at a lot of small details that combine to create the house’s particular architecture. Letting your eyes wander over the double-sided roof, the fieldstone or the stonework around the windows reveals a lot about the evolution of the house, but also about the history of these architectural elements.

An “anchor” is a piece of metal that prevents two parts of a structure from moving apart over time. Since the movement of the ground can cause a building to move apart, the purpose of the anchor is to reduce this effect by attaching itself to the floor beams and to the walls (Culture et communication Québec, 2001). In addition to holding various parts together, anchors are visible from the outside since part of the element protrudes from the exterior wall (Paré, 1993). Far from being only observable in one and the same version, they can take different forms. Thus, anchors in the shape of the letter S are simply called “esses” (Culture et communications Québec, 2015).

If you look closely, you can see that between the roof of the Hurtubise House and the stone walls, there are some anchors to hold these two structural elements together. Also, around the openings, you can notice other anchors called esses that are embedded in the stone walls. Around the front windows of the house for example, the esses were probably only used to hold the shutters that were installed at the time. It must be said that the shape of the metal letter S is often carefully forged creating an arabesque effect, which makes this small element very pretty on a frontage! Thus, they can also fulfill aesthetic purposes.

Since esses can also hold louvres, it would be interesting to demystify what the difference is between a shutter, a blind, louvre or a brace—terms that often seem to get mixed up…

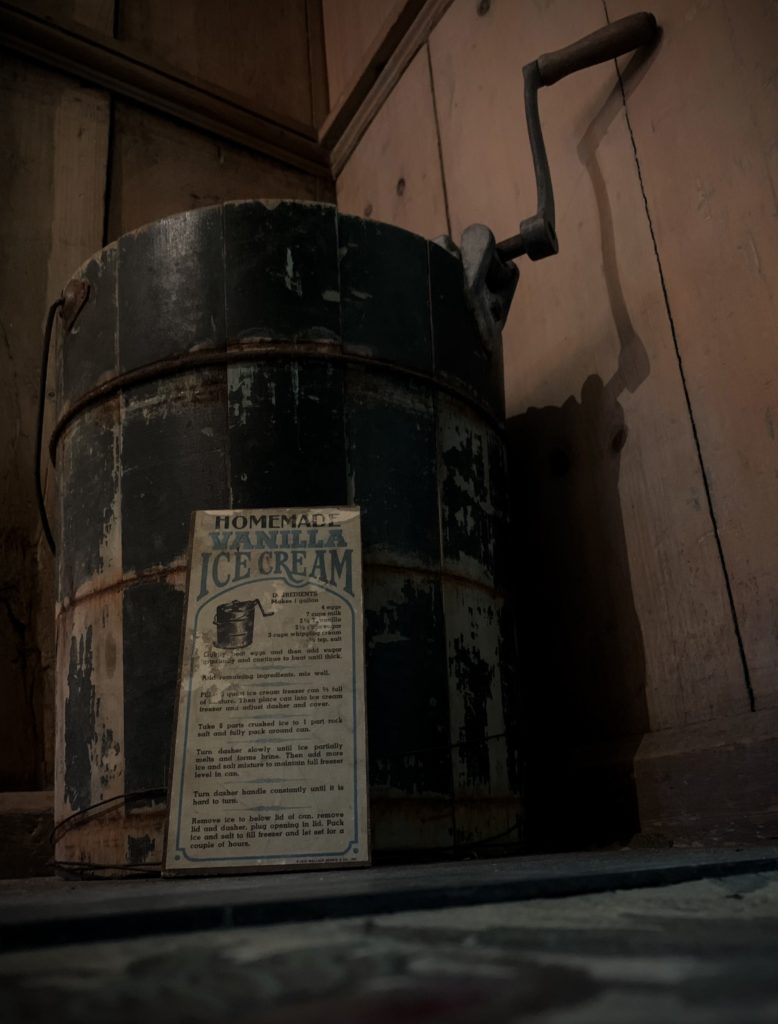

Perhaps we should start by establishing that shutters can never be seen outside: they are designed to be placed inside, close to the windows themselves. Braces, on the other hand, can be found outside, although they are solid panels that are placed in front of the windows to block the wind, for example. An expanded version of braces, louvres became popular a little later in history (City of Lévis). From the solid wood panel, long strips are removed to allow ventilation and a view to the outside. When the slats are mobile, the louvre is called a blind (Culture et communications, 2015). The Maison Hurtubise had louvres around the windows for a long time; now removed, they are displayed inside the house. A few pictures still remain to testify of this bygone era and to give us an idea of what it might have looked like.

You just have to open your eyes to find the esses or the hooks used to hang the louvres in those days. Will you find them?

Sources:

- Culture et communications Québec. (2015). Glossaire du vocabulaire de l’architecture québécoise. Culture et communications Québec. https://www.mcc.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/documents/patrimoine/Glossaire_vocabulaire-architecture-quebecoise.pdf

- Culture et communications Québec. (2001). Guide d’intervention en patrimoine. Culture et communications Québec. http://www.mrccharlevoix.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Guide-intervention-du-patrimoine.pdf

- Paré, G. (1993). Vocabulaire de la maçonnerie. Les Éditions de l’Équerre. https://www.institutdemaconnerie.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/vocabulaire_de_la_maconnerie.pdf

- Ville de Lévis. (s.d.). Composantes et modèles architecturaux. Ville de Lévis. https://www.ville.levis.qc.ca/developpement-planification/architecture-patrimoniale/composantes-et-modeles/?idfiche=34