Written by Ines Marchand

At the beginning of the 20th century, after the Victorian era, the West entered the Edwardian era under the reign of Edward VII. This period, which marked a significant cultural and social transformation, reflected this change with new sophistications and lifestyle. The Hurtubise family, who lived in Montreal at the time, witnessed these changes, particularly through their own fashion choices. Today, by analyzing the fashion trends seen in the Hurtubise’s family photos taken between 1900 and 1905, we will be able to place the family socially within this vibrant era.

First and foremost, it is necessary to learn about the overall fashion of the time. Edwardian fashion, existing from the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, brought significant changes to the Western world’s clothing styles. Montreal, which then experienced a cultural boom, positioned itself as a fashion center in Canada, with shopping streets such as Saint-Paul, Saint-James, Notre-Dame, and Sainte Catherine becoming hubs for fashion, fueled by emerging local manufacturers.

For women, fashion at the time was characterized by the S-shaped silhouette. As women increasingly entered the workforce, the Victorian silhouette gave way to this new, more practical form. To achieve this silhouette, meticulously designed undergarments were layered on the body. First, a shirt was worn along with underpants. Then, corsets, often custom-made, created the silhouette by accentuating the waist and hips. Contrary to popular belief, these corsets were neither uncomfortable nor restrictive; they offered support similar to modern undergarments while promoting an elegant posture. Over the corset, a corset-cover was worn, which further slimmed the waist while highlighting the bust, and petticoats, with their trailing effect, continued this S-shape below the waist. Finally, the outer clothing was added on top.

Daywear commonly included long-sleeved tops, lighter or heavier depending on the season, paired with skirts or dresses with similar shapes. Some details accompanied the silhouette, including puffed sleeves, which appeared at the beginning of the 20th century and became increasingly pronounced over the years. Buttoned skirts, also common, often transformed into pants when necessary for sports. Edwardian fashion, while concerned with aesthetics, marked a shift toward a more functional wardrobe for women.

Suit-inspired clothes for women also emerged as a notable trend, inspired by men’s clothing such as suits and buttoned shirts. Evening gowns, meanwhile, retained the S-shaped silhouette but were generally sleeveless and featured more pronounced necklines, reflecting a less modest fashion compared to daytime wear.

Accessories of the time added a touch of sophistication to everyday clothing. Hats, either boaters or adorned with feathers, were secured with hatpins. Leather heeled shoes, inspired by those of Louis XIV’s style, featured curved heels and numerous buttons.

Men’s fashion, though less revolutionary, saw notable adjustments. Three-piece suits, popular since the previous century, underwent few changes. Long coats, known as “tailcoats,” transformed into shorter and less formal jackets. Jackets, shirts, vests, and hats (boaters or bowlers) could all be removed depending on the degree of formality required. The collars of shirts at the time, known as “Imperial collars,” were straight and formal and could also be removed.

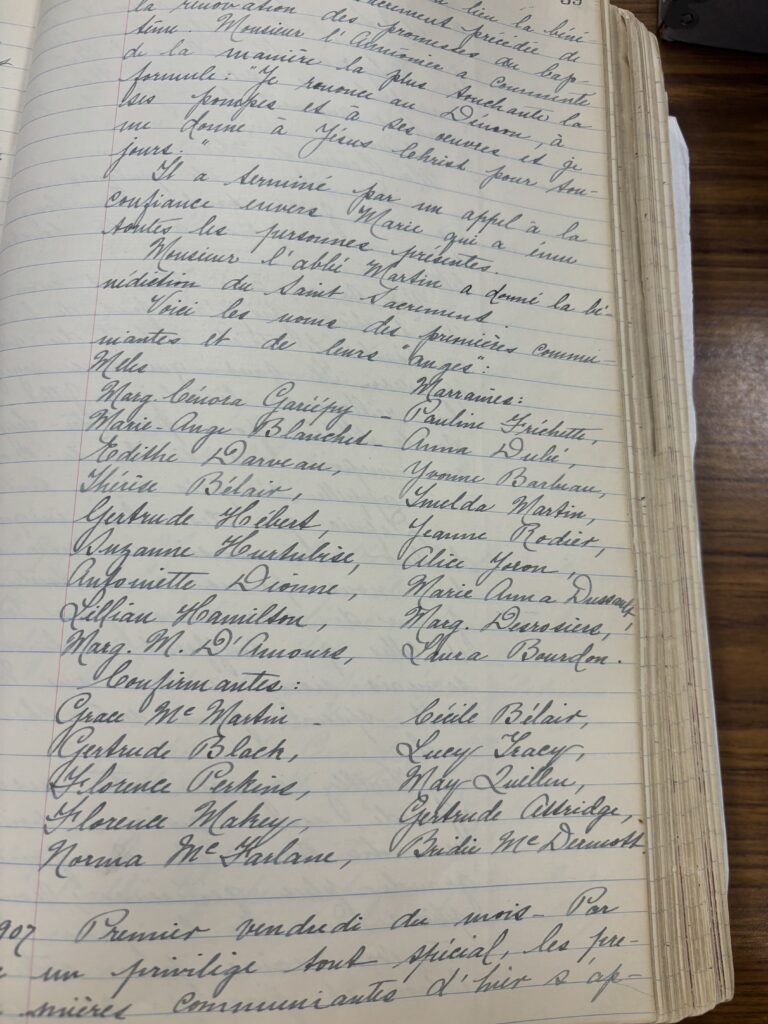

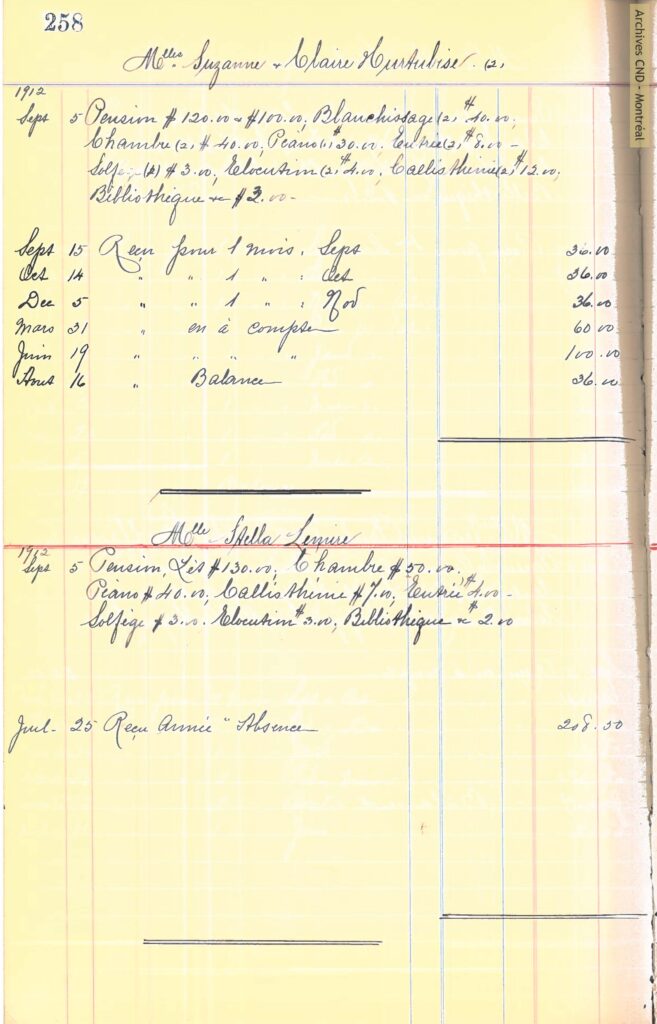

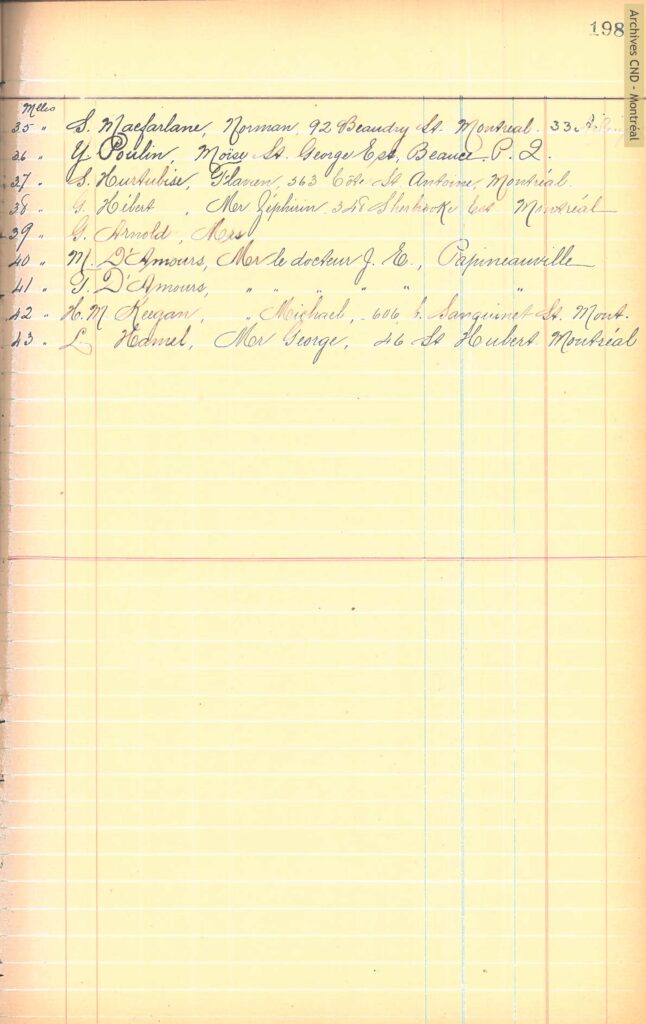

The Hurtubise family’s photos illustrate the emergence of Edwardian fashion. As a middle-class family interested in the arts, the Hurtubise family followed and participated in fashion through their own clothing. The photos allow us to analyze and understand how the last generation of Hurtubise kept up with fashion during a rich and evolving period in Montreal.

In this first photo, the three-piece suit worn by the men of the family reflects the fashion at the time. We can see jackets, shirts, and imperial collars. From one man to another, we can see the different ways of dressing the suit according to needs and desires. The simplicity and dark colors of the suits highlight the traditions at the time regarding men’s suits.

Our second photo highlights the generational differences and evolution in the suit and changes in jacket style. On the left, we can see a typical Edwardian suit, with a short jacket and imperial collar, while on the right, we see the vest and attached pocket watch accompanied by the tailcoat, typical of the 19th century. While the younger man on the left wears a boater hat, the older man on the right wears a top hat, also typical of the previous century.

The woman in the photo wears a skirt and blouse that seem to imitate the three-piece suit while remaining feminine, along with a bowler hat originally worn by men. Her belt is decorated, and, knowing that wristwatches did not become popular until much later in the 20th century, we ca hypothesize that her necklace also served as a watch.

The family’s elegance is also demonstrated through the women’s clothing in this photo, particularly through the hidden seams and buttons, creating an illusion of length in the silhouette and showcasing the quality of the garments. For the woman seated in the middle, the seams are likely on her side, while the other two women around her probably have the buttons on the back of their dresses. The busts are also accentuated, and the puffed sleeves well-presented.

Details can be found in accessories such as tall hats adorned with feathers or on certain parts of the dresses. The hair, meanwhile, is styled high on the head in a bun, but less tightly than in the previous century. These details highlight the move towards a more refined and sophisticated aesthetic of Edwardian fashion.

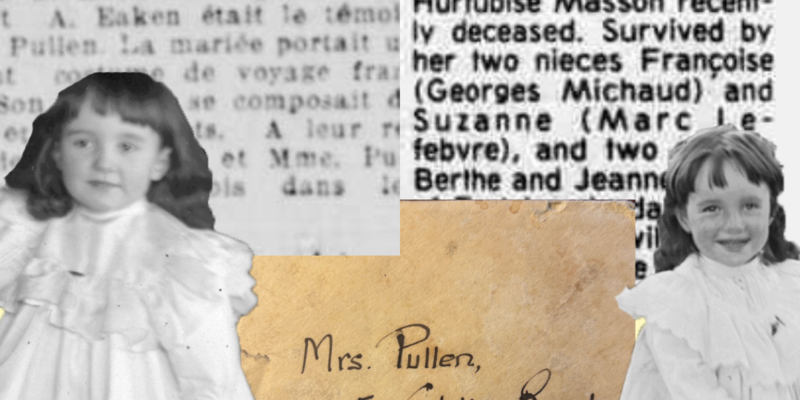

The young girl in the photo, dressed like an adult but with loose hair, light clothing, and a relatively short dress, demonstrates an Edwardian fashion also present in children. This aesthetic, evolving with age, allows us to estimate the child’s age range.

All these trends and details are found in this last photo: puffed sleeves, three-piece suits, embroidered details on the clothes, light and slightly masculine tops paired with long skirts, buttoned boots, and high-styled hair. The two young girls also wear lighter but longer dresses, with styled hair, indicating a more advanced age range.

However, the clothes worn by the Hurtubise family do not just reflect their concern for style but their social status as well. Fashion choices, such as hidden seams and ornated hats, along with the photographic setting, show an investment in fashion and a desire to maintain a certain appearance. The Hurtubise family, though middle-class, managed to combine aesthetics and functionality, as well as purchased and handmade items, while reflecting the fashion trends of the time.

Indeed, details in the photos show a relatively high social status and financial means. In our first photo, the refined elegance of the colors and details in the clothing suggests a certain purchasing power and a lifestyle that allowed for wearing light-colored clothes. White or cream-colored clothes were a sign of social status, their maintenance requiring that the wearer stain them as little as possible, which in turn translates to a lack of physical work. This is a sign that intellectual work among the members of the Hurtubise family would have been prioritized, a sign of elevated social status.

The second photo illustrates the family’s effort to stay in tune with the fashion of the time, with the woman wearing what resembles a masculine suit, a common cut in women’s fashion.

In our third photo, the hidden seams and buttons of the garments reveal costly craftsmanship. Although these may not be at the peak of fashion, this attention to detail still demonstrates a desire to follow Edwardian fashion. The hats worn further accentuate this desire.

Finally, our last photo shows the family’s desire to stay fashionable throughout the seasons. The clothing seen is indeed designed to be both elegant and seasonally appropriate. We still see the puffed sleeves, leather boots, tied-up hair, light-colored clothing for the younger girls, and light-colored tops and shirts decorated with lace. This adaptation reflects a particular attention to image and a certain skill in achieving the desired appearance.

Other details, however, support our theory of handmade elements in the clothing of the Hurtubise family. For example, in the first photo, the young girl wears a dress with a lace collar and sleeves adorned with English embroidery. The embroidery, less fine than the lace, indicates a modification made by the family to add a touch of distinction. This shows a need for personalization, as buying ready-made clothes with certain details would likely have been too expensive for the family.

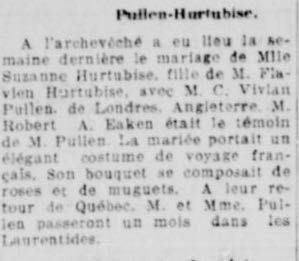

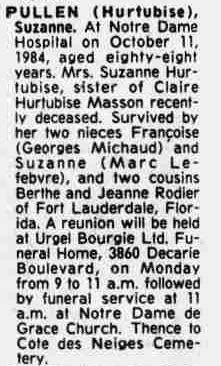

Thus, the clothing of the Hurtubise family reveals not only their concern for style, with their neat and elegant appearance, but also their financial capabilities and a desire to be part of high society. The family, despite their appreciation for the arts, remained middle class. It is therefore likely, as seen earlier, that they combined handmade and purchased clothing, opting to modify quality items to achieve desired effects. Being active members of society, it is possible to speculate that the Hurtubise family frequented the fashion shopping streets such as Saint Paul, Sainte Catherine, Saint James, and Notre Dame. The Hurtubise may have obtained their linen and cotton from Dick John or Canadian Colored Cotton Mills & CO on Saint James Street, their corsets from Barry Bros and Compton Corsets on Notre Dame and Grenier C.J on Sainte Catherine, their jewelry from Eaves Alfred on Notre Dame and Eaves Eamund on Saint James, and finally their shoes from Real LTD on Notre Dame. They may also have frequented tailors such as LaMontagne and Morgan & Henry on Sainte Catherine.

In the end, the analysis of the clothing and photos of the Hurtubise family gives us an insight into their social status and lifestyle, as well as that of any family of the same social class at that time. Through the details of their clothing, from the seams to the ornate hats, it is clear that the family, though middle class, sought to reflect a sophisticated and elegant image. Thus, their clothing reveals not only a desire to participate in high society despite limitations, offering insight into their place in Montreal society of the time, but also an affinity for the arts, a demonstration of their ability to express themselves through the blend of photography and fashion, a subtle yet fascinating narrative that unfolds through the photos taken by Dr. Hurtubise.

References:

All the clothing pictures, apart from the Hurtubise ones, come from the McCord Stewart Museum archives in Montreal.

Franklin, Harper. “1890-1899”. Fashion History Timeline, Last updated Aug 18, 2020.

Reddy, Karina. “1900-1909”. Fashion History Timeline, Last updated Aug 18, 2020.

Laver, James. “Costume and Fashion: A concise History”. Thames and Hudson, 2014.

Milford-Cottam, Daniel. “Edwardian Fashion”. Shire Publications, 2016.

Archibald, Kristy. “Montreal’s Garment District Past and Present”. Nuvo Magazine, 2021. https://nuvomagazine.com/daily-edit/montreals-garment-district-past-and-present

BAnQ Numérique. « Collection d’annuaires Lovell de Montréal et sa région, 1842-2010 ». Last consulted in August 2024.