Written by Ines Marchand

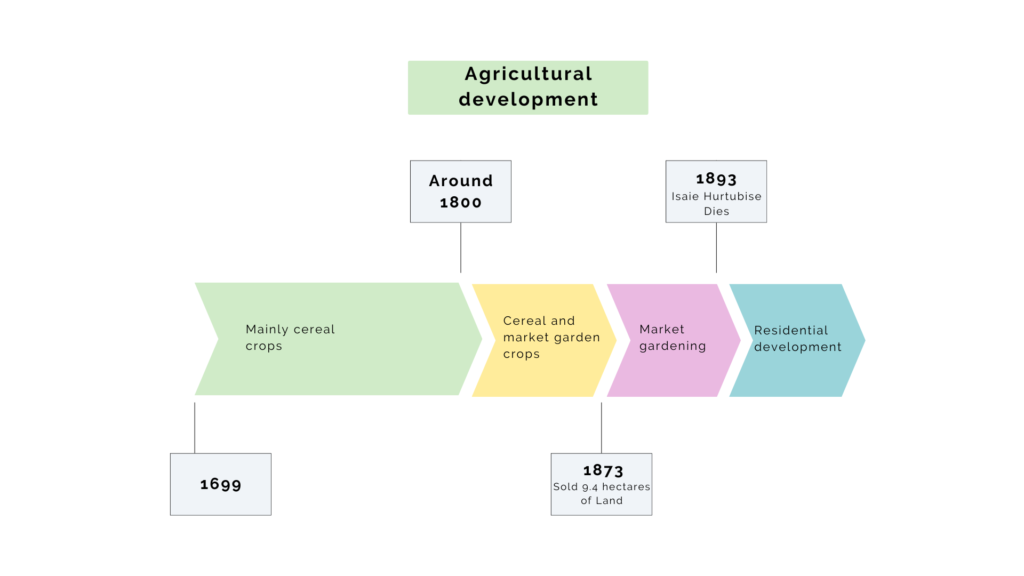

In 1699, Louis Hurtubise acquired agricultural land in New France, Canada, and transformed his family into farmers. Since then, the Hurtubise family’s wealth has flourished, surpassing neighbouring farming families. Their prosperity is still visible today through the architecture and composition of the Hurtubise House, which still stands in Westmount. The Hurtubise family’s agriculture practices evolved over time, going through phases that have been found to correspond with the different agricultural phases observed in Quebec between 1600 and 1910.

With the mass arrival of French settlers in early 1600s New France, agriculture and farming were the main occupations for settlers, following the example of Louis Hebert, the first agricultural settler at the time. Agriculture and colonization were heavily encouraged then and throughout the rest of the century. Another important figure at the time was Jean Talon, who introduced hemp cultivation and livestock breeding in New France.

The Hurtubise family was no exception. They joined the other settlers in practicing agriculture and farming. From 1699 to 1800, their farming would have primarily consisted of cereals. They cultivated oats, wheat, and barley. They also seemed to cultivate plants like peas, more likely for the family’s consumption. They also owned animals that served for domestic purposes. They owned nine pigs, four horses, eleven cows, and three bulls, which they fed thanks to their oat crops. Their surface of the land which was able to be farmed was 3 by 29 arpents (one arpent equals 192 feet), and their production included 38 bushels of wheat, 42 bushels of oats, 15 bushels of peas, and one arpent of tobacco for personal use, which emerged in 1798. During this period, the family’s main farmers were Louis Hurtubise (1699-1703), Jean Hurtubise (1724-1766), and finally Pierre-Jérémie Hurtubise (1766-1792). As in all Quebec farming families, the land succession was done from father to son. Thanks to the location of their land on the slope of “West Mount,” water flowed down and through their land naturally, promoting ideal conditions and minimizing crop losses.

After 1793, English-speaking settlers settled around New France, introducing potato farming. However, agriculture remained the main activity of French-speaking settlers.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Quebec faced agricultural difficulties, a period nicknamed The Agricultural Crisis of the 19th Century. According to historical theories, the crisis was caused by wheat production declining in Lower Canada, giving Upper Canada the upper hand in wheat production and selling. The French settlers, mainly from rural backgrounds, lacked knowledge of modern agricultural techniques. This led to a decline in production and a dramatic impoverishment of the peasants, who then turned to subsistence farming.

During this agricultural crisis, we can observe the first shift in Hurtubise’s agriculture: the incorporation of market gardening. According to our data from 1861, the cultivable area now included 32 acres of field crops, 8 acres for pasture, 3 acres for the orchard, and 2 acres of woodland, or 45 acres in total. Their production, at the time, was 30 bushels of wheat, 30 bushels of barley, 25 bushels of peas, 100 bushels of oats, 600 bushels of potatoes, 100 bushels of carrots, 3 tons of hay and 300 bushels of butter. The Hurtubise family still had animals: six cows, including three milk cows, five horses, and four pigs. The farmers then were Pierre-Jérémie (son) Hurtubise (1798-1829) and Antoine-Isaïe Hurtubise (1829-1878).

This shift suggests that despite their land’s fertility and low losses, the Hurtubise family adapted its practices with the rest of New France. The incorporation of new crops, while arguably unnecessary in their case, anticipated a need for subsistence due to the economic decline for farmers in Quebec. However, there is no trace in our archives today of a decline in wealth among the Hurtubise family during this period, suggesting that they were more fortunate than their counterparts.

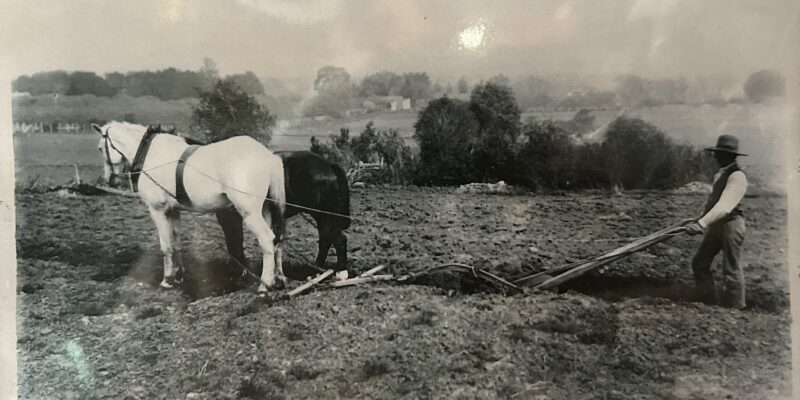

Although we do not have precise traces of the family’s daily life at the time, we can still imagine a typical day at Hurtubise House. The day at the farm began early, with the men caring for the milk cows and the chickens’ eggs. Mornings were devoted to market gardening, maintaining and harvesting fruits and vegetables. The rest of the day was dedicated to the fields, where cereal crops still had to be planted, sown, and harvested. During this time, the women and children stayed together in the house’s main room, preparing copious meals to feed the whole family, especially the men, who required a lot of energy.

Due to the decline of wheat, the agricultural crisis forced many farm families to change their practices. Although agriculture was still present in Quebec, it was no longer as prosperous as in the rest of Canada. Towards the end of the 1800s, Lower Canada, or Quebec, turned to the dairy industry to meet its needs.

At this time, the sixth and last Hurtubise generation lived in Westmount. This generation abandoned agriculture to turn to studies, like Dr. Léopold Hurtubise, the house’s last owner. Records from 1873 show that after Antoine-Isaïe sold 9.4 hectares, the remaining 7.1 hectares were used to grow chamomile, cucumbers, ivy, chives, potatoes, leeks, turnips, onions, flax, strawberries, thyme, radishes, nasturtiums, beets, parsnips, mustard, corn, pumpkins and peas. The remaining animals were one cow, twenty-four chickens, three ducks, and four horses used for carriage travel. Isaïe Hurtubise, son of Antoine Isaïe, was the last farmer, from 1878 to 1893. The remaining crops were used only for the family’s needs and, therefore, had no financial purpose.

Today, only the Hurtubise House and its archives bear witness to the existence of this family and their daily lives as farmers. Nevertheless, a commemorative garden was built on site to trace and represent the former lands of the Hurtubise family on a smaller scale.

References:

Dick, L., & Taylor, J. (2024). Histoire de l’agriculture jusqu’à la Deuxième Guerre mondiale. Dans l’Encyclopédie Canadienne. Repéré à https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/fr/article/histoire-de-lagriculture

Lavertue, R. (1984). L’histoire de l’agriculture québécoise au XIXe siècle : une schématisation des faits et des interprétations. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 28(73-74), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.7202/021660ar