Written by Danka Davidovic –

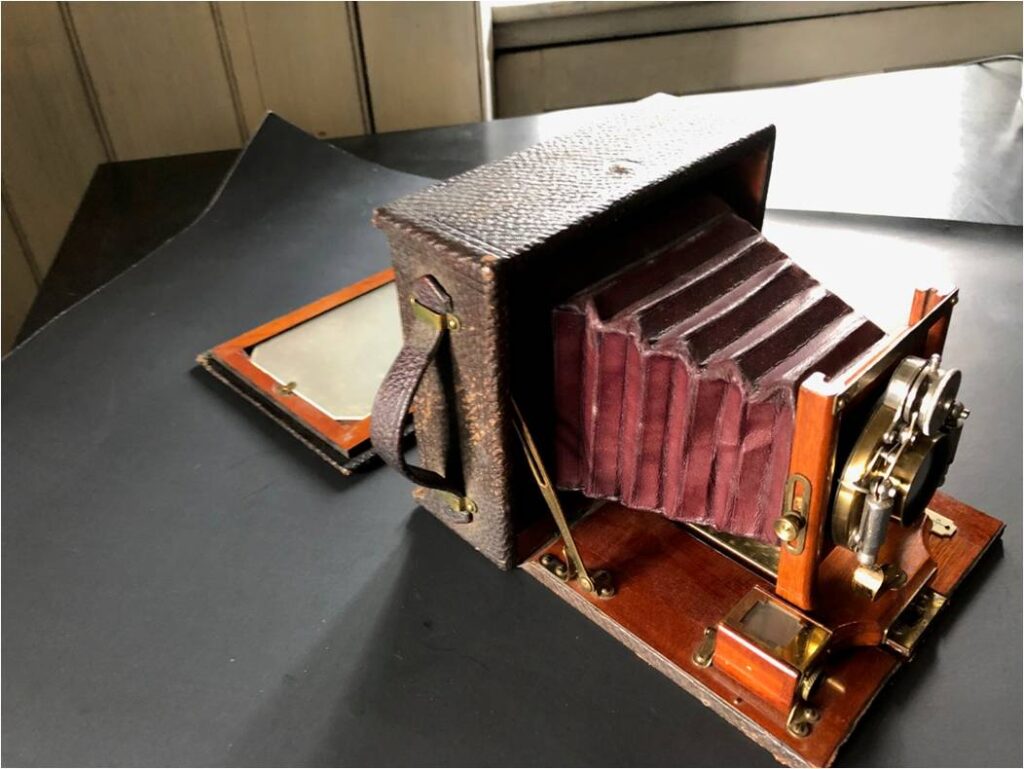

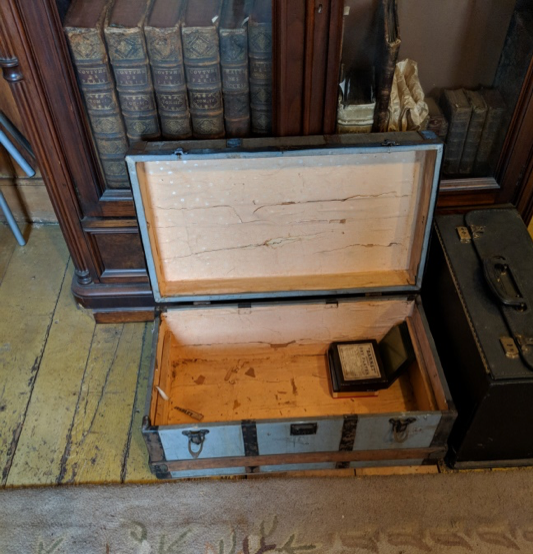

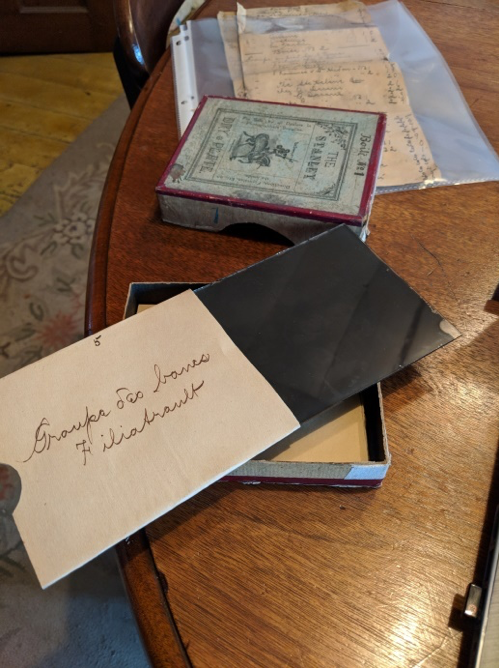

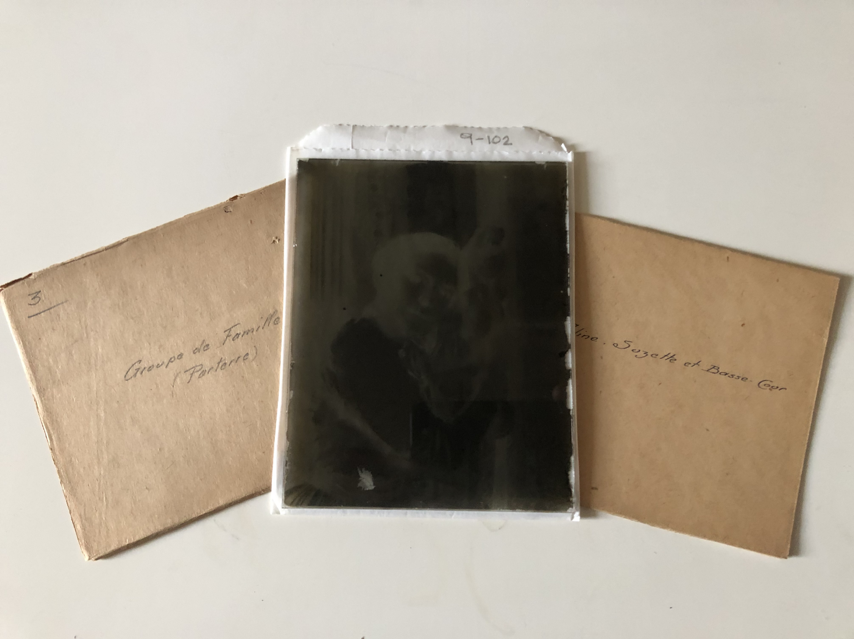

The CHQ’s extensive collection of stereoscopic photos transports you through the unpaved (and sometimes snow-covered!) streets of 19th century Montreal. Popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, stereoscopy was renowned for producing 3D images. This process involved taking two pictures at slightly different angles that mimicked the distance between the eyes, so that, when placed side-by-side and viewed through a stereoscope, the image looked to be 3D (Vaillancourt, 2015).

The CHQ’s stereoscopic collection captures a time of intense economic activity in what is now Old Montreal. Despite the city’s growth beyond Saint Antoine Street by this point, Old Montreal continued to be an important hub in this time. This exhibition allows you to explore the city street-by-street and neighbourhood-by-neighbourhood during this period. See the newest addition to Sainte-Catherine Street around 1840-1850, when the street would begin its gradual growth into a commercial area with the opening of the Morgan and Ogilvy department stores in the last decade of the 19th century.

Witness the migration of the city’s institutions from the unsavoury industrial old town, especially around Lachine Canal, to the heights of the city around 1860. The Grey Nuns on Dorchester, the Hôtel-Dieu on des Pins, and the college of Montreal on Sherbrooke, are all examples to which the current city still bears witness.

Admire the splendour of the “Golden Square Mile”, populated by the luxurious residences of the city’s wealthy businessmen starting from 1850. Some, like Harrison Stephens, settled on Dorchester Street, while others came to prefer the area leaning against the mountain. You can still admire some of these houses today!

William Notman, James Inglis, James George Parks and more provide a captivating look at the city in this online exhibition prepared by Yves Guillet. Click here to download the English PDF.

Source:

- Vaillancourt, N. (January 8, 2015). Avant la télévision 3D : la stéréoscopie. BAnQ. https://blogues.banq.qc.ca/instantanes/2015/01/08/avant-la-television-3d-la-stereoscopie/